1 、要了解这家品牌设计公司的服务理念 2 、要了解这家品牌设计公司团队 3 、要了解品牌设计公司的规模 4 、要系统查看品牌设计公司过往的成功作品 5 、要参考品牌设计公司合作的客户档次。

首先要看这个 品牌设计公司的文化。简单地说就是服务理念,一个公司的文化定位决定着这个企业的格局和素养,比如明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计的“帮助客户成功才是明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)的成功”,这是一个有大格局的品牌设计公司所具备的。

其次,看这家 品牌设计公司是否拥有高度协作的策划和设计团队。品牌设计不是一个设计师能完成的,从调研分析,策划定位、到品牌设计再到后期监管,需要有强大的专业团队做后盾。高效、专业的团队协作是专业的品牌设计公司所必备的。所以,优质的 品牌设计 VI 设计公司有着明确的分工,从而保证品牌设计工作完成的整体性和时效性。明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划成总监说过:只有规模性的优秀的设计公司,才会有着明确的专业分工,否则一般来说都是不可信的。

第三,看规模,如果我们注重品牌塑造,当然要委托一家专业的 品牌设计公司,自然要看它的整体设计实力和发展状况,我们要选择正规的有规模和有专业分工的 品牌设计公司,而不是小作坊、小团队、小工作室,因为他们很不稳定,虽然价格比较低,但是没有保障,说不准某天就消失了,最起码的,应该看看这家品牌 VI 设计 公司成立多少年了,办公环境和场所怎么样,这是对一个品牌 VI 设计 公司的最起码的考量。

第四,看作品,对一个优秀的 品牌设计公司的考察主要是放在品牌设计公司的成功案例方面,有没有获得过奖项也是重要考核的指标,从品牌设计公司以往的设计案例中,可以大致地了解到这家 品牌设计公司的实战经验,进而可以清晰地了解到这家 品牌设计公司的实力。一个企业的 VI 设计工作并不是任何人都可以随随便便完成的,优秀的设计作品来自于设计者优秀的综合素质,就像同一件衣服不同的人穿上的气质是不一样的。一个 品牌设计公司是否优秀,可以从案例作品中考察出来。

第五,看合作客户,如果一家专业的 品牌设计公司合作的都是不知名和不起眼的客户,毋庸置疑,肯定不会有操作大项目的经验,就像一个人没有设计过五星级酒店一样,他肯定不会知道怎么装修五星级酒店,也肯定不会能达到五星级要求的设计高度。

所以说选择一家优秀的 品牌设计公司并不是一件简单的事情,需要仔细的考察。

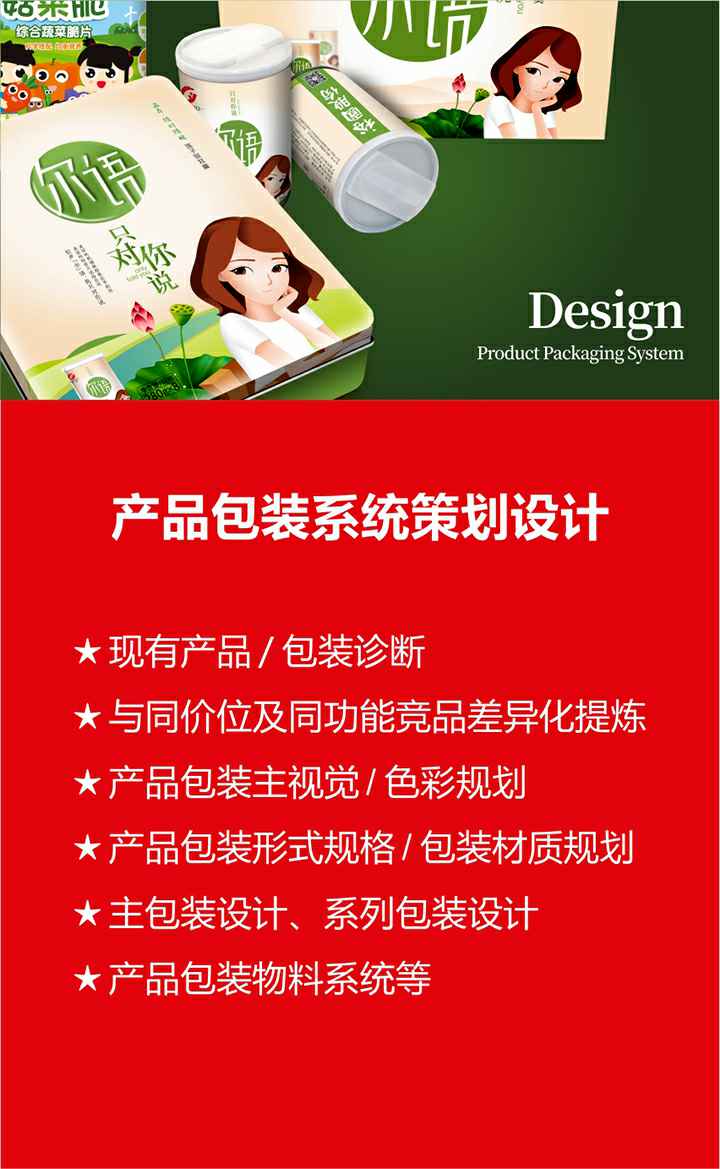

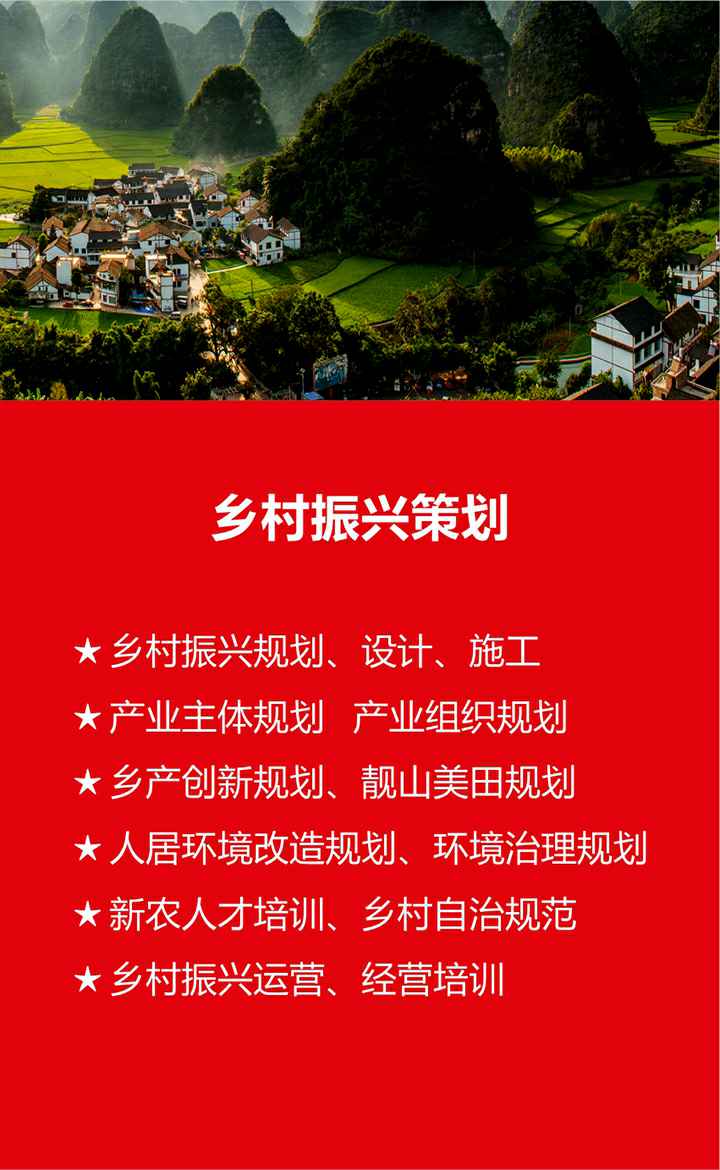

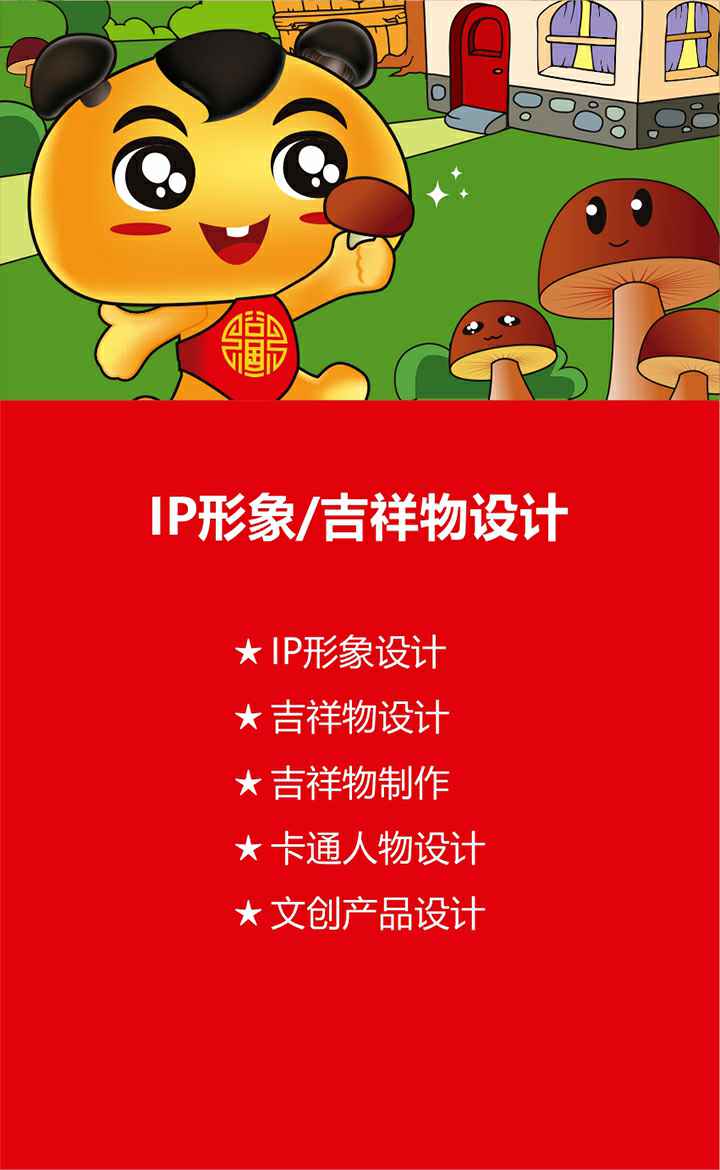

明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计是华中地区影响力品牌策略与设计机构, 2001年创始至今明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计一直专注于品牌策略与设计,服务内容包括 ( 品牌形象策划、 CIS系统全案导入、品牌设计、标志设计、 logo设计、商标设计、 VI设计、包装设计、画册设计、茶叶包装设计、酒类包装设计、礼品包装设计),其作品多次获得设计界大奖。

明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计以顾客为中心,为客户创造精准、可行、极具商业价值的品牌形象。数年来,明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计坚持高水准的服务标准,凭借对市场趋势敏锐的洞察,和对消费者、企业形态深刻的理解,服务了客户数百家,跨越众多行业。一切为了销售,否则我们一无是处!

和明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)合作的意义在于,明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计笃信创意与实效的双峰,明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划存在的唯一理由是帮助客户成功!发展我们客户的生意。明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计给客户提建议时绝不考虑自己的短期利益,而是把客户的事业当做自己的事业来规划,当做自己的公司来工作。这也是明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)拥有的最大财富。明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计带给客户的是一流的创作,是既可以促进销量,又可以让品牌得以持久发展的优秀品牌设计。

明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计是优秀的 品牌设计公司, 明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)设计将创作放在一切工作的首要地位。我们清晰地给出我们的意见,但我们完全尊重客户决定选用什么方案的权利,这是他们的利益所在。 我们致力建立与客户互利共赢的伙伴关系。我们谨言慎行,客户不会欣赏泄露他们秘密的合作伙伴。 我们也不会把客户的成就归功于己。抢客户的镜头是一种恶劣行为。 我们认真对待新的生意,特别是由现有客户带来的新业务。

长期的默契合作,是高质量服务和创意的保障。 我们抱着不急不燥的专业研究精神来为您工作在 品牌设计领域,我们不是艺术家,我们是利用艺术元素和审美知识,帮助品牌和商品创造更大商业价值的专业人才。 我们为客户提供的不仅仅是作品,而是商业服务和专业信息的支持,以及推广建议 。

明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)( www.booer.cn )始于 2001 年,是华中地区专业具有十八年丰富成功经验的策划设计公司,明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)策划设计擅长 CIS 系统全案导入、 VIS 设计、企事业机构标志设计、 LOGO 设计、商标设计、画册设计制作、包装设计制作的品牌设计公司 。 明博官方网站-明博MINGBO(中国)能为你提供超值的服务。